Kriegsmesser: learn more about weapons and their use

Kriegsmesser, from a fencer's perspective.

Part I

The common misconceptions

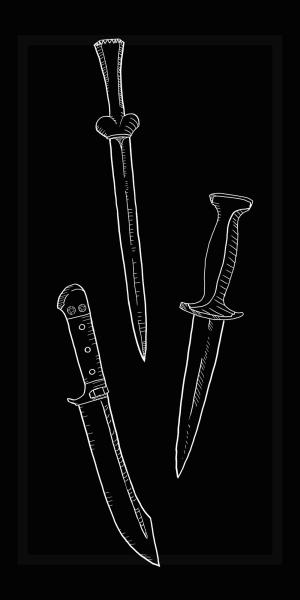

In the previous series of articles, we covered the meteoric rise to prominence of the dussack during the 16th century, learning that there’s more to it than complex hilted blades simply replacing the messer. This brings us to another well know 16th century weapon type, closely connected with landsknechts: the Kriegsmesser. In a cruel twist of fate, no manuals appear to have been written that explicitly describe the use of these largest of knives. The coming weeks, we will be attempting to experimentally test some often suggested styles of fencing for the kriegsmesser.

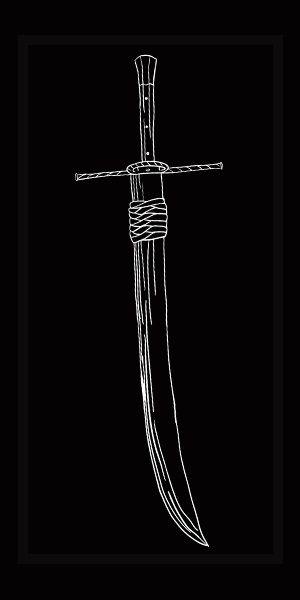

Falke Kriegsmesser, designed by Landsknecht Emporium

This first article will quickly examine some often encountered misconceptions about kriegsmessers. Let’s start with nomenclature. Although the variations of ways to refer to messers could (and in time will) be the subject of a dedicated article, I will limit myself to just the term ‘Kriegsmesser’ here. In our modern minds, the kriegsmesser or ‘war knife’ is a weapon wielded by professional warriors, meant to be used two-handed and up to 1.5 meters long.1 Although I would not be surprised if the term was occasionally in use during the 16th century, we should be wary of assuming that in the past people stuck to such rigid categorisations. There’s a number of problems with this definition. First off, the term ‘war knife’ or equivalents do not always show up as such in sources. Often enough, soldiers carrying messers are rather described as being armed with ‘long knives’.2

Landsknecht with a Kriegsmesser

Source: wikimedia.com

The other problem is that a kriegsmesser doesn’t appear to be always meant as a two-handed weapon. In the Triumph of Maximilian we find landsknechts with kriegsmessers and targes for instance.3 Additionally, the length of such weapons wielded by landsknechts rarely exceed 120 cm. The previously quoted dimensions would seem like a bit of an exaggeration. In plenty of period images, we find soldiers being armed with kriegsmessers that appear to be between 90 and 120 cm long and most originals seem to support this observation4. Giving a truly fitting definition of kriegsmessers in a short article would be undoable, but at the very least, we can conclude that they make up a far more varied category of weapons than often assumed. For the purposes of the this series, we will consider a kriegsmesser to be a knife, roughly 90 – 120 cm in length, distinguished from what is colloquially called a langes messer by the simple expedient of being carried by soldiers rather than civilians.

Join me for the next instalments, where I will be testing a number of often suggested possible ways to handle kriegsmessers. As a great mind once said, the difference between science and messing around is writing it down, so I’ll be documenting my experiments in some detail. Stay tuned!

1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Messer_(weapon) (04-11-2020)

2 Cornelia Nicolasina Wilhelmina Maria Glaudemans, Om die wrake wille (Leiden 2003)

3 Pierre Terjanian, The last knight. The art, armour and ambition of Maximimilian I (New York 2019)

4 https://www.hammaborg.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/zabinski_mitchell_fritz_leckuchner.pdf,

https://www.zornhau.de/dinkelsbuhl-first-steel/,

https://historische-waffenkunde.de/Downloads/Beispieldatei-Langes%20Messer-2009-G-3.pdf,

http://www.vikingsword.com/vb/showthread.php?t=15053&highlight=messer (04-11-2020),

Part II

The weapon

Kriegsmessers are in many cases shorter than we would think, being in a range of different lengths that could be reasonably wielded with one or both hands. In this instalment of our ongoing series on wielding kriegsmessers, I will be examining one particular source and seeing how it holds up when the messer is just that bit longer than expected. That source will of course be Andre Paurenfeyndt’s Ergrundung Ritterlicher Kunst der Fechterei. The source is divided in multiple chapters, of which the second chapter deals with the messer. Paurenfeyndt is quick to add though, that his advise on fencing should also work for an assortment of other one-handed weapons. From experience I can tell that even using sideswords is no problem with this treatise, so why not try a kriegsmesser?

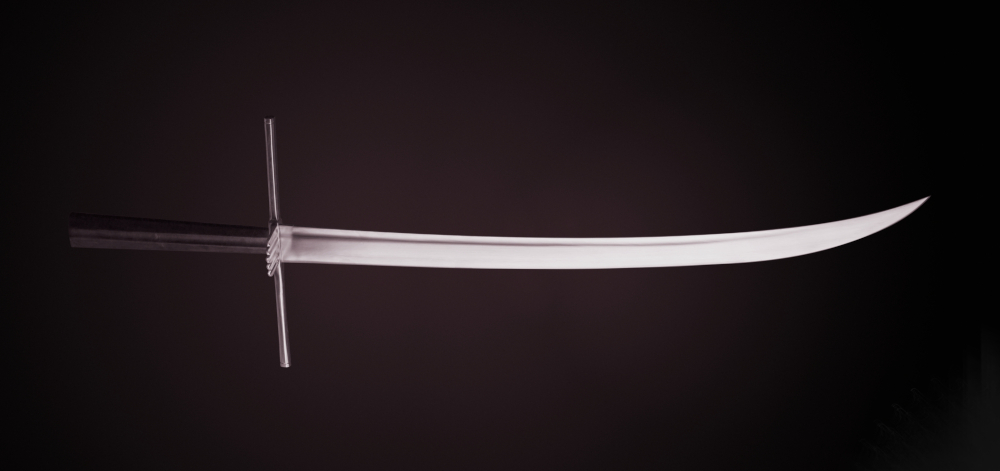

Sparring Kriegsmesser by Landsknecht Emporium

I designed the experiment as follows: since we had to perform it with whatever weapons we had at our disposal, I decided to give the agent in every play the kriegsmesser and the patient a Dorothea tassack. The kriegsmesser is a blunt model, coming in at 118 cm and weighing 1485 g. I selected a number of plays from the Ergrundung, to represent as many aspects of Paurenfeyndt’s one-handed section as possible. The plays were then filmed. Additionally, I have included my observation on them.

The first set of plays and counters (G2) comes from the first page of this chapter and deals with a strike from above from a low position, performing either a hanging parry or a thrust to the hand. The counter to both is a feint to the other side. The basic cut is quite easy to perform. The counter feels a bit more awkward though, but whether that has to do with blade length or an unwillingness to go faster and risk hitting harder is not fully clear. A lot of core stability is required to perform any play with the kriegsmesser safely. When such considerations are taken away though, it is surprisingly easy to keep the blade going. Making big cuts that flow through guards works really well with the kriegsmesser.

The second set of plays (G3) starts with a thrust and strings together a number of cuts afterwards. The counter is very common in this treatise: take it away with the back of the knife. Both the play and the counter once again make it really clear that keeping the flow of the cuts going makes the plays from Paurenfeyndt quite easy with a kriegsmesser.

The third set (G4) starts in a point down, low guard and deals again with a strike coming in from above. The options to hit include a thrust and a windtstraich. Both are viable, but especially the thrust felt really easy to perform. The blade length was ideally suited for it, and although performing it against a lighter shorter blade gave a big advantage, I think that even against a longer blade it would have been easy to thrust.

The fourth can be found on page (G3) and is a particular close play, that still requires blade work exclusively. Colloquially it is known as the Turkenczug, name after the mounted backward sabre cut that was associated with Ottoman soldiers. This one was difficult to do with the kriegsmesser, because both fencers step forward in this play. Because of the length of the blade, it naturally rather turned into a hook over the wrist or an überlauffen (not bad, but not the play as described).

The fifth and final play (I) is Flugel Lesen and was included as a close play with the off-hand involved. Especially because the off-hand needs to be used in a rather complex way, crossing over the knife-hand, I expected this to be difficult. After a number of attempts it clicked though and the length of the blade was no real hindrance.

In conclusion, I would say that it is entirely reasonable to take a 16th century treatise for one-handed cutting weapons, and use it as a guide for fighting with a kriegsmesser. It may not be explicitly written with that goal in mind, but Paurenfeyndt’s Ergundung is, with some minor adaptation, a useful source for it.

Stay tuned for the next articles in this series, as I’ll be examining other possible fencing styles.

Part III

Comparison to the greatsword

Can we twirl this war-knife? In the previous instalment of this ongoing series of articles on the Kriegsmesser, I examined Andre Paurenfeyndt’s system as a basis to work from and found that it a very plausible idea. Some people suggested in comments that a Kriegsmesser could also in a way be treated as a ‘montantified’ Messer, effectively using techniques designed for greatswords. I have been wondering about this myself as well, so let’s dive in shan’t we?

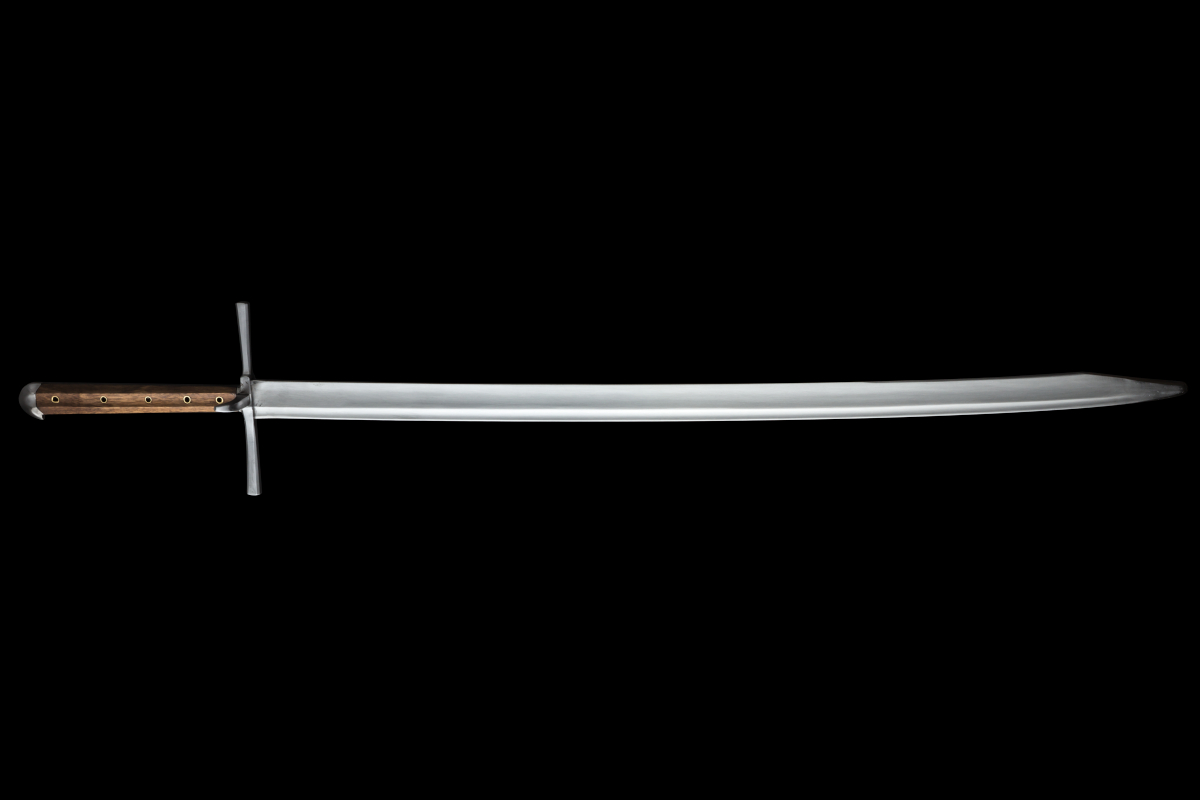

As last time, the Kriegsmesser used is a prototype version of the Rotmilan sparring Kriegsmesser (118cm, 1485g). For comparison I am using a Regenyei armory spadone nr. 3 (160 cm, 2350 g). The methodology is slightly different than last time though, as fitting with these times, the experiment was performed without a partner. Because this experiment is also an explorative foray into the vast and unknown realm of the Kriegsmesser, I decided to stick to a single source for the techniques. I selected the treatise that Dom Diogo Gomes de Figueyredo wrote in 1651, partially because it is the most well-known source for Iberian montante and partially because it comes with a great variety of different plays to choose from. I first wanted to go through two rules to compare overall mechanics of the different weapons. After that, I chose the remaining rules based on their different applications. Each rule was first performed with the montante and afterwards with the Kriegsmesser for comparison. Below I listed my findings on each one.

-

Rule 1 simple: being a simple combination of cuts from below, the mechanics didn’t feel very different, despite the rather big disparity in weight and length. Additionally, I did find in this case that the big range of motion to efficiently perform the cuts at speed with the montante really helped with the kriegsmesser as well.

-

Rule 3 simple: a very nice doubled cut from above from both sides. This rule also reveals the similarities in handling between greatsword and kriegsmesser, and seems to confirm my observations of the first rule.

-

Rule 6 simple: this rule is meant to serve the user against another montante, by taking snipes at the legs and hands of an opponent who is similarly armed. It’s here that the difference between the greatsword and the kriegsmesser starts to tell. The kriegsmesser is much lighter and therefore it is simply easier to quickly change the direction the weapon is going. It is noticeable when during the experiment I fail to swing the kriegsmesser all the way back to the position in front of the head, without it affecting the flowing movement all too much. It is quite simply not necessary to use the same range of motion with the kriegsmesser as with the montante. This makes a real difference when engaging someone with the same weapon, in which case a more direct approach would be more likely to be successful.

-

Rule 8 simple: working mostly against shieldbearers, this rule brings in a very nice strike through the middle that requires serious range of motion to perform at speed with a greatsword. It is once again not really necessary to make such a big sweep with the Kriegsmesser. Here another issue pops up as well. It would not be unheard of, from 1500 onwards to see shields combined with swords that have blades that are as long as those on Kriegsmessers, making this play a rather risky one. The advantage in reach that a greatsword would have, is simply not present with the Kriegsmesser.

-

Rule 14 simple: dealing with polearms, be it in the air or still in the hands of the wielder is a good skill to practice. Figueyredo seems to have thought so at least. This is one of the few times a fencer is actually encouraged to make a spinning attack and in this context it makes sense. It allows one to get away from the trajectory of the weapon, cover the distance and set up for the counterblow. Once again, the Kriegsmesser could afford to be far more economical with movement.

In conclusion I can say that it is possible to wield a Kriegsmesser like a montante. Why would anyone want to though? With a Kriegsmesser of common measurements, around 120 cm, there is no need to utilise such a big range of motion as the montante requires. Furthermore, at that length a lot of the rules become really risky and serve no real purpose anymore. This is of course not to say that no Kriegsmesser was ever handled like this. Some originals were larger than the example I used. Some past fencer or Landsknecht might have had a personal preference for sweeping cuts. However, this experiment does suggest that techniques meant for greatsword are really not optimal for Kriegsmessers.